كتاب روابط اجتياز لـ منصة منظمة الصحة العالمية لتبادُل المعارف بشأن السل

8.1 The role of M&E

M&E play important roles in patient care and in assessing national programmes and the global response (Fig. 11). Accurate recording and reporting of programmatic data inform managers about the immediate outputs and outcomes of programme services as well as the larger impact of resources invested into a programme. If services are adequately accessed, activities are conducted in a timely manner, and expected results are achieved, it is likely that the overall goals will be met. When properly implemented, M&E should provide health-care providers and programme managers with information on how many contacts are in a TB patient’s household and how many of them were effectively evaluated, or, how many people who were offered TPT in an ART clinic decided to take it and how many of those who started TPT continued it until the end.

Fig. 11. Use of health data at different levels of the health system

8.2 Monitoring PMTPT

As several activities under PMTPT – such as contact investigation and preventive care of people with HIV – overlap with screening for TB disease and involve similar at-risk populations, M&E should be aligned to promote synergies and limit duplication. It is important to ensure that individuals who are at greatest risk of developing TB are systematically identified, and, once TB disease has been excluded, offered TPT to improve both their individual health and the community disease burden. Programmatic implementation and scaling up of TPT require strengthening of each element in the cascade of care, starting from identification of the target population to provision and continuation of TPT (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Critical numbers of people to be monitored at each step in the TPT pathway

No., number; TPT, TB preventive treatment

a if CXR and tests for TB infection are not used, this is the number of people with no clinical evidence of TB disease; if CXR and tests for TB infection are available, this is the number with no clinical or radiological evidence of disease and with a positive test for TB infection. In some individuals at risk TPT may be medically contraindicated.

8.2.1 Indicators for monitoring PMTPT

Generation of indicators is a critical outcome of recording and reporting. It is usually done every 3 months at regional and national levels, depending on the number of people being monitored. Data on TPT services are aggregated at regular intervals and reported for monitoring progress. If an electronic case-based data system is available, with nationwide coverage, data at lower levels may be aggregated at any required frequency to evaluate programme performance.

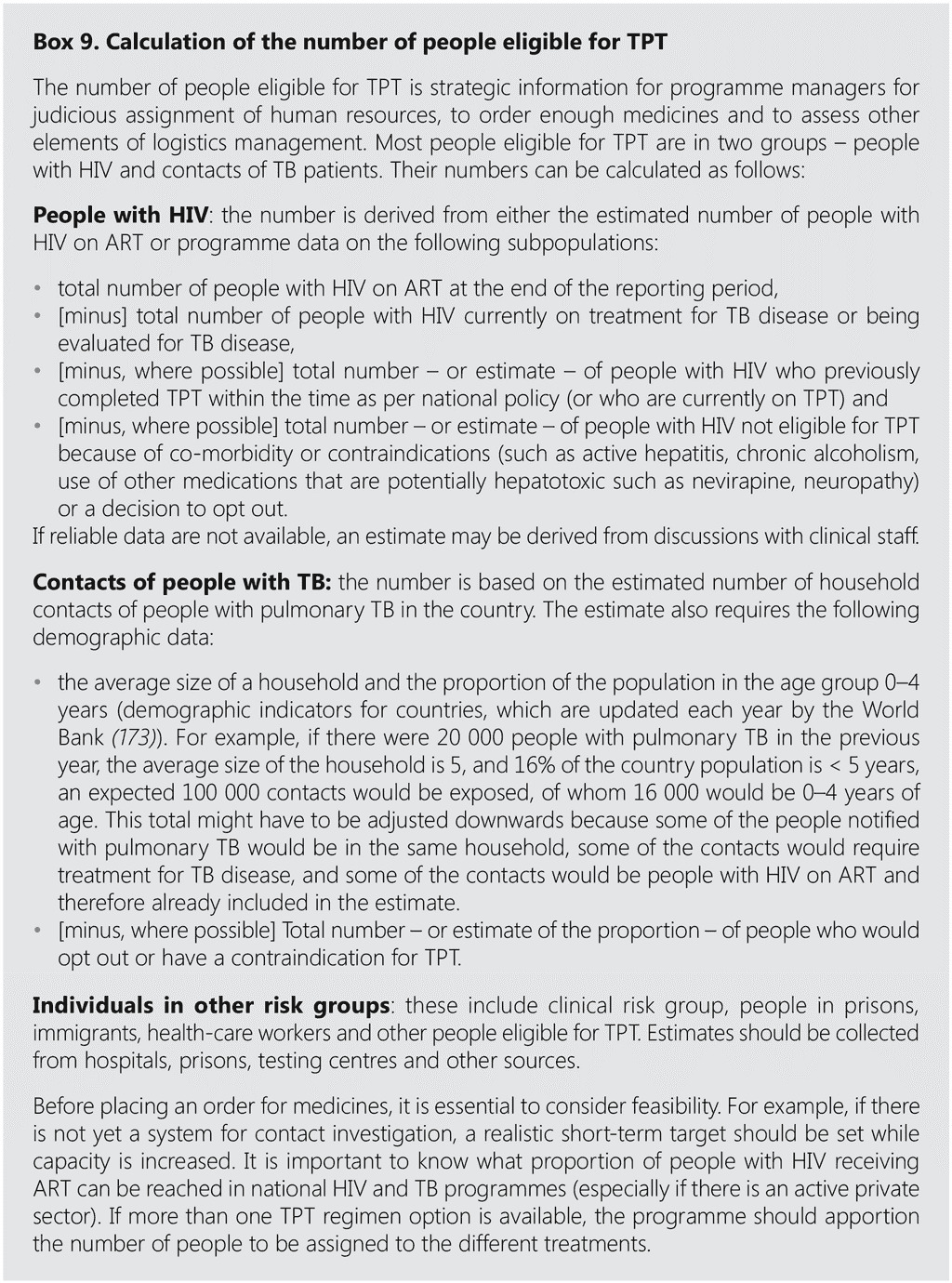

Principles for estimating the numbers eligible for TPT are listed in Box 9.

Table 10 lists the minimum indicators for PMTPT that should be measured. The programme may also decide to monitor other activities, such as the coverage of testing for TB infection among people targeted for testing during investigation of eligibility for TST. Use of metrics of the timeliness of screening and implementation of TPT in household contacts of people with pulmonary TB are discussed in section 2 (Box 1).

8.2.2 Data requirements for monitoring TPT at individual level

A minimum set of variables proposed to be collected at individual level is shown in Box 10. A more extensive list of variables is provided in Annex 6 to help programmes organize evaluation of the contacts of an index person with TB in a household or other setting.

Table 10. Indicators for monitoring PMTPT

3HP, 3 months of weekly rifapentine plus isoniazid; 3HR, 3 months of daily rifampicin plus isoniazid; 6H, 6 months of daily isoniazid monotherapy; 6Lfx, 6 months of daily levofloxacin monotherapy; ART, antiretroviral treatment; MDR/RR-TB; multidrug-/rifampicin-resistant TB; TPT, TB preventive treatment; UNHLM, United Nations High-level Meeting on TB

a See text and Table 9 for proposed thresholds of completion by regimen.

Programmes may collect additional data to review certain programmatic aspects, such as adherence to medication. If drug safety cannot be monitored satisfactorily in routine pharmacovigilance systems, data on adverse drug reactions (frequency, organ class, severity and response to withdrawal and rechallenge) can also be included. Attention should be paid not to overburden the data collection system with details that are not used systematically for patient care and programme management. It may be tempting to do this when electronic data systems are installed, but it should be avoided, as it is a waste of resources and demotivates staff.

When capacity for routine M&E of minimum indicators is still being built, ministries of health and national programmes may consider periodic analyses of medical records, which can be done by simple sampling. Adherence to medication and drug safety may also be investigated in such a survey. In many settings, service data on people with HIV on ART are captured in electronic data systems, which allow a variety of analyses with unique personal identification in various data systems (such as a cohort analysis of people with HIV newly enrolled in HIV care who were screened for TB, evaluated for TPT eligibility, started on TPT and completed TPT). The availability of unique personal identification enables de-duplication of entries and increases the reliability of data for programme management

8.3 Monitoring TPT completion

It is important to monitor TPT completion in individual care as well as for programme management. An electronic data capture tool should record details of treatment outcomes for everyone starting on TPT. TPT may be considered completed when an individual has taken at least 80% of doses within the expected duration of the regimen and the rest of the doses within an extended time equivalent to one third of the normal duration and remains well or asymptomatic during the entire period. Table 10 shows how these timings apply to all recommended regimens. Other outcomes of TPT to help improve programmatic performance are proposed in section 7.

8.3.1 Data recording tools

National TB and HIV programmes use patient cards, medical histories, case files or electronic medical records as sources of information on TPT services. Challenges to scaling up TPT services are the requirement for diverse data, which are often available only in paper-based records, and the involvement of many health-care service providers. Programmes for monitoring PMTPT usually capture data on paper, such as lists of contacts investigated in a household, or additional columns in an ART register to record TPT initiation among people with HIV. These tools are reviewed periodically to derive indicators, usually manually. Printing and updating of paper records adds to the burden of health-care workers.

Data from TB programmes on people with TB disease who require treatment, including ART, are increasingly being recorded electronically and are used to generate M&E indicators as well as to follow patient responses. Many programmes, however, are yet to develop systematic electronic data collection mechanisms to generate indicators. WHO promotes development of existing or new electronic systems to capture the data necessary for PMTPT care and monitoring to generate indicators automatically. Hand-held devices such as smartphones are particularly suitable because they can capture data from sites critical to PMTPT activities, such as the home of an index person, an ART clinic, a hospital, an occupational health centre or an immigration screening service (see Box 11).

With increasing numbers of people being evaluated for TPT, the many available TPT regimens and the importance of disaggregation of various subpopulations, it is important to invest in electronic recording systems for accurate quantification and procurement of consumables. The information is also useful for planning human and financial resources. As global access to affordable hardware, software and connectivity increases, real-time monitoring of the performance of PMTPT components becomes more feasible. Dedicated M&E staff should be assigned and trained to coordinate and build national and subnational capacity in use of data for decision-making. Countries should dedicate a budget for digitizing data collection and reporting and request funding from donors if necessary.

8.3.2 Data confidentiality

Optimal TPT and care involve disclosure of personal information to the health-care system. This sensitive information must be treated with the utmost confidentiality, in accordance with the professional code of conduct. It should be shared only with people who require it, who are usually those who are providing direct care. All documents containing confidential information must be securely stored. Duplicates and unnecessary documents should be discouraged and destroyed when no longer required. Computerized databases that contain sensitive information should be protected by coded passwords and encryption, and only certain users should be granted access. Entries should be immediately de-identified after data aggregation. Personal details should be removed as soon as possible from data collected and reported when they are no longer required. Care should be taken in making referrals to other services, such as when information on an individual is transferred from one care facility to another (either manually or electronically). Each programme should have a policy to ensure the confidentiality of personal data, and, if there is a national policy, it should be enforced in all parts of the health sector. Information on how their data are handled should be included in counselling provided to people who are offered TPT. Just as they are empowered to opt out of TPT, their decision about use of their personal information should also be respected.

8.4 Supportive supervision

Good supportive supervision is an essential element of routine M&E in both central and district health facilities. It includes checks on the quality of data recording and reporting, including inspection and validation of a person’s medical files and data collection tools for the validity and completeness of recording. National programmes may provide a standard checklist for assessing data quality and use along the cascade of care, from identification of the target population for TPT initiation to completion. The frequency of supportive supervision depends on resources and requirements, and closer monitoring may be necessary to ensure data quality when PMTPT is relatively new. Supervisory visits may also be used to collect data for HMIS reporting. At least once a year, the supervision team should conduct an audit of data quality in routine monitoring systems. This should involve members of both TB and HIV programmes and possibly others, such as prison health and occupational health services.

تعليق

تعليق